Before we tackle the main question of this post, whether immaterial goods are suitable for owning or not, it makes sense to look at the ways such goods can be created. For simplicity, let’s consider all immaterial goods [1] - from literature and music to technical inventions to program code - as either inventions or discoveries.

Now there is this old debate whether inventions should be considered discoveries too. Maybe the only difference between them is that the former need a much more sophisticated discovery process. Can only some humans invent the wheel or the microprocessor or would - for instance - an alien civilization at some point in time end up with very similar ideas? Probably yes.

I allow myself therefore to simplify the situation further and discuss - hopefully without loss of generality - only discoveries of knowledge.

For this purpose I will choose my favorite metaphor, „drilling for water“.

So let’s not waste time and start drilling now!

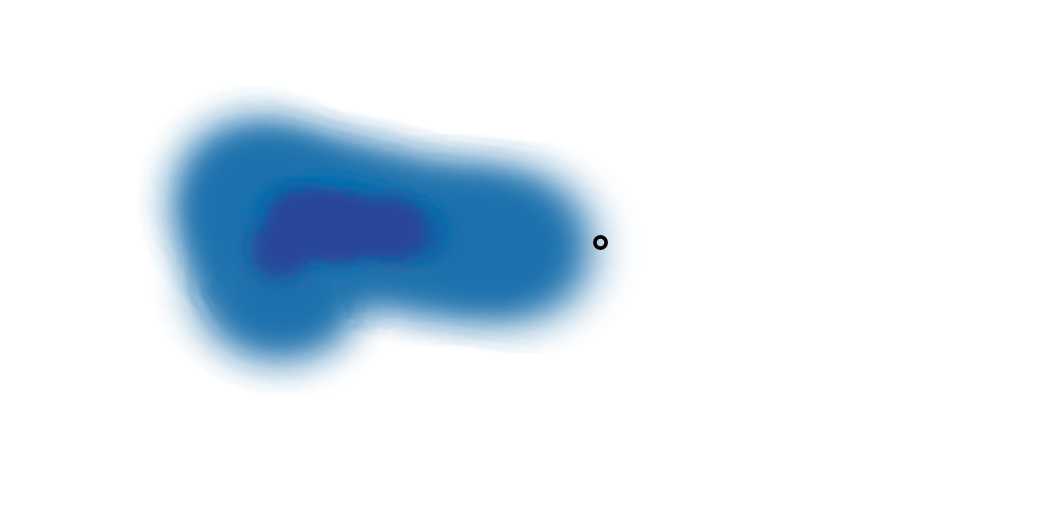

Imagine the situation shown in the following illustration. It’s a map (i.e. top view) showing groundwater resources.

Important: note that only we have access to this precious map, the guy who has to search for the water doesn’t!

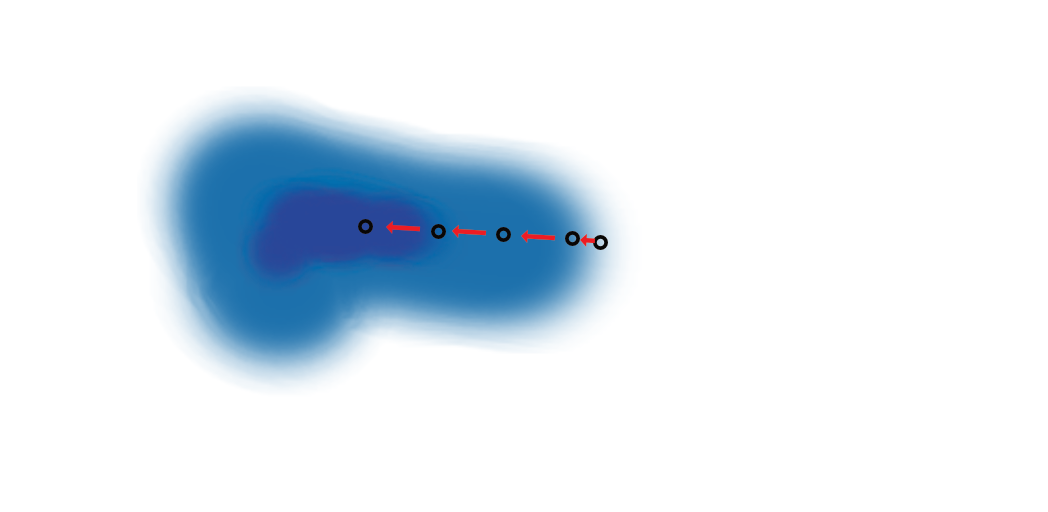

Now imagine that the geologist is drilling somewhere and he finds that indeed some water enters the drilling hole. He now observes carefully from which direction the water enters the hole [2]. Then he puts the next drilling hole some smaller distance away from the original hole in this direction. Then he repeats the process. It is clear that - sooner or later - he will be able to tap into the big reservoir at the perfect location:

Mathematicians and machine learning engineers recognize this idea as gradient ascent. It often works very well and we owe things like incredibly perfectly crafted Japanese samurai swords (and also modern AI!) to this technique. Let’s call it also exploitation [3].

But there is a limitation. It might allow you to slowly transition from a crude iron sword to the perfect samurai sword made out of layered carbon steel, but it will not allow you to find/invent gunpowder and the matchlock firearm. Why is this so?

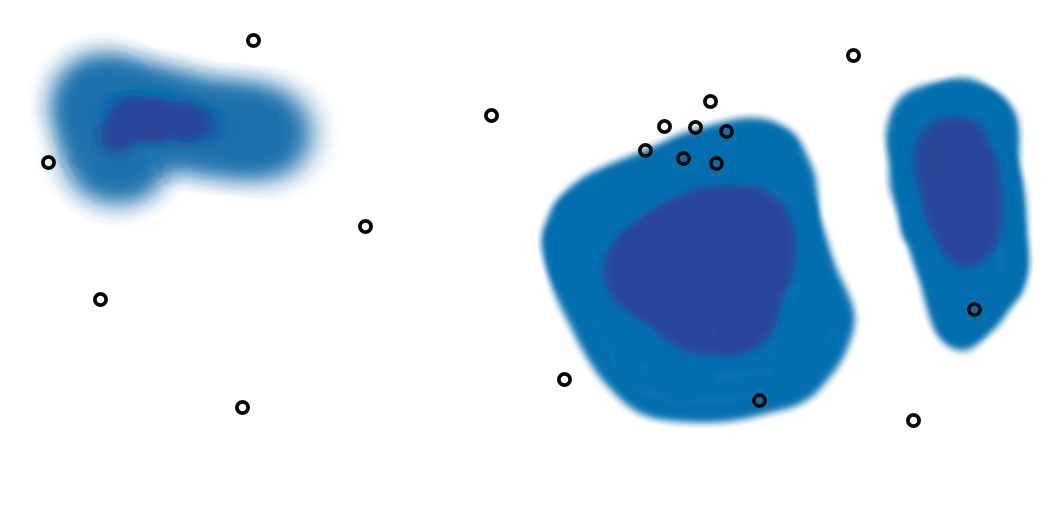

Look at the following extended map:

While the reservoir we have discovered before is all good and nice, there are actually two other much larger reservoirs at other locations. Mathematicians would say: before we have found only a local maximum. How can we make sure we find the better locations too (the so called global maximum)?

What we could do is just some random drilling everywhere. If we have some success at a certain location, we increase the density of drilling holes in this area:

Mathematicians and machine learning engineers recognize this idea as genetic algorithm. It allows us to discover any reservoir, but again there is a problem: as we see in the area with dense drilling, we actually won’t find the very perfect spot easily. And if we don’t drill at very many sites, we might not find the best spot at all.

Let’s call this method exploration [3].

Now we see that a combination of exploration and exploitation will yield the best results. Exploration is used to find a rough estimate for a good drilling site while exploitation, as a second stage, is used to find the really best spot.

It becomes also clear now why Japanese culture traditionally focuses more on exploitation: exploration requires much more drilling. It is more promising if a large number of „geologists“ is available (such as in the connected countries of the main continent). For a small island it was more efficient to do gradient ascent on already known knowledge instead.

In an effective use of both methods, exploitation comes always second. Therefore, the person who focuses on exploitation creates the most valuable product or knowledge. The more you drill using gradient ascent the better the output becomes. But each drilling actually builds on all the previous drillings.

Therefore, if knowledge can be owned, doing gradient ascent / exploitation is highly incentivized. Only fools would waste their time doing exploration. Of course, patent laws were created to mitigate this problem. But many results of exploration are still not patentable (this is especially true for pure discoveries, like laws of nature).

Many startups and large software/infrastructure companies are built on vast amounts of open source software. Their enormous value comes only from a very thin layer of „exploited“ software they put on top of this stack. Their own contribution is actually minimal compared to the contribution of society.

This is how owning intellectual property creates wrong incentives. It creates a strong preference for exploitation compared to the equally important exploration.

[1] There is no suitable word (I think) for what I mean here. The term immaterial goods is actually used for things like patents and copyrights which only make sense in the context of owning. The term „intellectual property“ has - of course - the same problem.

[2] I have no idea if this is how geologists drilling for water actually do this. Forgive me (geologist) father, it’s only a metaphor!

[3] Not to be confused with the same terms used in reinforcement learning: the meaning here is different.

Image: KarenPouls / Pixabay (nice! thank you!)

Follow me on X to get informed about new content on this blog.